When Victor Anjos co-founded Data for Good in Toronto, he probably only dreamed that the not-for-profit could use data to help feed more hungry people, to warn about potential genocide, or to raise money to research a cure for cancer. Five years later, it’s done all of those things and so much more.

The organization has grown to seven chapters across the country and more than 2,500 volunteers. What began in Toronto with Anjos and partner Joy Robson in 2013 has expanded to Vancouver, Edmonton, Calgary, Regina, Ottawa, and Montreal. The mission of the organization is to use data in the service of humanity. Rather than squeeze out more corporate profits, these do-gooder data scientists hope to find ways to use their powers to help improve people’s lives.

Now Anjos is the first winner of the Canadian Advanced Technology Alliance’s (CATA) AI Leader of the Year Award. Jointly sponsored by SalesChoice, CATA, and IT World Canada, the award recognizes consistent leadership resulting in the creation and international acceptance of a world-class AI product or service.

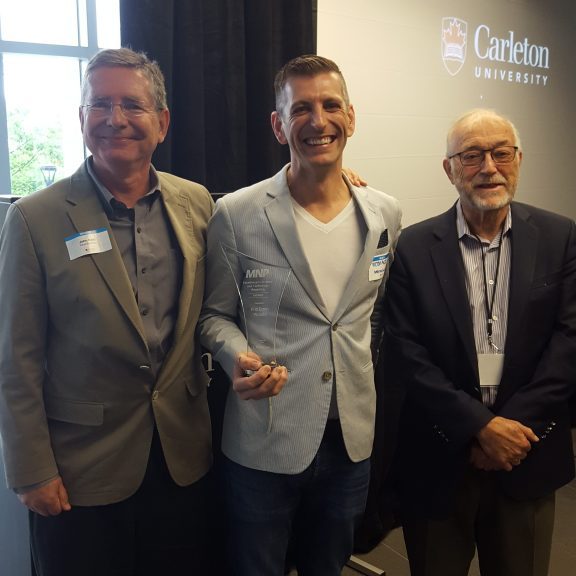

Victor Anjos (centre) poses with CATA John Reid (left) and John ApsSimon, vice-president of research at Carleton University.

The award comes at a moment when Anjos is ready to take the next step with Data for Good. It’s grown organically across the country over the past several years with very little money to help the organization along. Soon it will work on a process for reporting requirements at its different chapters. Then it will seek donors to hire staff for those chapters. Then it could find ways to harness all of the data it’s accessing across the country into a more unified effort.

“We’ve seen very similar data sets many times,” Anjos says. “If we can get not-for-profits to work together and agree to work from the totality of data, we can do very powerful things for them.”

At the moment, Data for Good chapters deal with one project at a time. Other non-profits and charities come to it with a data problem that needs to be solved and its volunteer data scientists get to work on crunching the numbers. Anjos shared three examples of work that he – and other chapters – have been involved with.

3 ways data has been used for good

1) Feeding the hungry. Toronto’s Second Harvest is a charity that delivers fresh food to those in need. In 2016, it served 200,000 people, about 40 per cent of them children and youth. It supplied the Data for Good Toronto chapter with its operating data on how much food it collected (tonnage) and the class of food (eg. protein or carbohydrate).

Second Harvest optimized its truck routes to pick up fresh food for the hungry.

The data scientists created a data visualization of food that moves through the city at different times of the year. “They saw there was a lack of protein at certain times,” Anjos recalls. “Especially in the summer months for some reason, people weren’t giving as much food.”

It also was able to optimize Second Harvest’s truck routes. By solving the classic “traveling salesman” problem of having to visit numerous points on a map in a day (in this case to pick up and drop off food), Data for Good was able to reduce the time it was taking and the amount of fuel burned.

“Because of the savings on time and on fuel they were able to afford another truck and driver,” Anjos says.

2) Fighting cancer. The Terry Fox Foundation came to Data for Good with a more typical data set – donor data. With the information on who was donating and when, the data scientists were able to recommend methods to appeal to new donors, or increase the frequency that existing donors were giving money.

The Terry Fox foundation raises money to research cancer.

“Someone who has given three gifts of $100 is likely to be amenable to a monthly donation plan,” Anjos says as an example.

Anjos points out that this type of situation, where a not-for-profit client is providing a few spreadsheets of donor data, doesn’t yield enough data to provide machine learning techniques. Instead, members use tools like Tableau and D3JS to visualize donor data and reveal patterns.

3) Predicting genocide. The Sentinel Project is an NGO that works to prevent genocide around the world by creating an early-warning system to alert the world to a potential genocide and providing a toolbox of strategies to prevent it. It provided operational data to Data for Good in order to have it build predictive models for when genocide will occur.

One effort by The Sentinel Project is to create a safe space in North Kivu in the Congo.

In testing, the data scientists succeeded in creating a robust prediction engine.

“When you’re training machine learning you’re training based on past data, and then you test against a part of that data that you held back from the data model.,” Anjos explains. “There was very high accuracy in the model we created.”

The Sentinel Project has since taken that model and added to it for improvements. It also served as a point of inspiration for launching other projects, such as a conflict tracking system, and Hatebase, a repository of multi-lingual hate speech that could help predict violence against minorities.

More projects like these are ahead for Anjos and the rest of the Data for Good team. Also in store this year is a revamp of the organization’s website, one that Anjos says will bring a different look and feel, helping the not-for-profit portray itself as a structured and established organization.